|

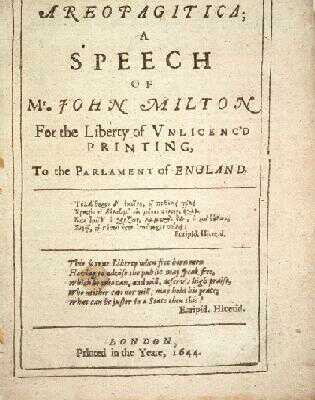

Areopagitica

History of Licensing

Though Milton himself declared

that the requirement for book licensing was an invention of the

"Council of Trent, and the Spanish Inquisition engendring

together," and denounced the licensing order of 1643 as "the

immediate image of a Star-chamber decree," and otherwise

attempts to give the impression that licensing is thoroughly

un-English, something imported by the bishops in 1637 (the date

of the Star Chamber decree), this is not entirely true. Though

the enforcement of licensing in England had been uneven at best,

and there had been long periods during which the policy of

licensing was not enforced at all, the policy was far from new.

In 1408 Archbishop Arundel's Constitutions (confirmed by

Parliament in 1414) order that "no book . . . be from henceforth

read . . . within our province of Canterbury aforesaid, except

the same be first examined by the University of Oxford or

Cambridge . . . and . . . expressly approved and allowed by us

or our successors, and in the name and authority of the

university . . . delivered unto the stationers to be copied

out."

Henry VIII in 1530 forbade the printing of "any book or

books in English tongue, concerning holy scripture, not before

this time printed within this his realm, until such time as the

same book or books be examined and approved by the ordinary of

the diocese." He also required approved books to carry "the name

of the Examiner" as well as that of the printer. In 1538, Henry

extended licensing to books of all kinds, transferred the

licensing authority from the church offices to the Privy

Council, and prescribed the form of the imprimatur. Later

monarchs such as Edward (in 1551), Mary (in 1553 and 1558), and

Elizabeth (1559, 1566, 1586) issued decrees which continued this

system. King James confirmed this system in 1611 and 1613, and

during the reign of Charles I, the Star Chamber issued its

now-infamous decree on July 11, 1637. This decree made it a

general offense to print, import, or sell "any seditious,

scismaticall, or offensive Bookes or Pamphlets." It also forbade

forbade anything to be printed which had not first been licensed

and entered in the Stationers' Register. Nothing could be

reprinted without being re-licensed. In all cases the full

signed imprimatur was to be printed; the names of the printer

and the author were to be printed as well. The decree also

limited the number of master printers to twenty, while

specifying the number of presses, journeymen, and apprentices

each could have. The decree made it an offense to work for an

unlicensed printer, or to operate an unlicensed press.

The Star Chamber was abolished on July 5, 1641. This

left the press virtually free from regulation. On January 29,

1642, the House of Commons ordered that printers should neither

print nor reprint anything without the name and consent of the

author. This order, sometimes referred to as the Signature

Order, is taken by Milton in Areopagitica as Parliament's

original policy concerning licensing of the press. The

Parliamentary licensing order of June 14, 1643, is therefore

taken by Milton as a reversal of this "original" position.

This order was designed for "suppressing the great late

abuses and frequent disorders in Printing many false forged,

scandalous, seditious, libellous, and unlicensed Papers,

Pamphlets, and Books to the great defamation of Religion and

government." It ordered that "no Order or Declaration of both,

or either House of Parliament shall be printed by any, but by

order of one or both the said houses: nor other Book, Pamphlet,

paper, nor part of any such Book, Pamphlet, or paper, shall from

henceforth be printed, bound, stitched or put to sale by any

person or persons whatsoever, unless the same be first approved

of and licensed under the hands of such person or persons as

both, or either of the said Houses shall appoint for the

licensing of the same."

Milton's attack on the Licensing Order had no effect on

Parliament's policy; in fact, Parliament re-asserted its

position in separate Orders on September 30, 1647, March 13,

1648, and September 20, 1649. Milton himself served as licenser

of Mercurius Politicus in 1651. For a brief period of 15

months, between 1651 and 1653, the Commonwealth government

experimented with an unlicensed press; however, the Rump

Parliament revived licensing in an order of January 7, 1653.

|

Milton's Response to the Licensing Order of June 14,

1643--Areopagitica |

Introduction

- It can’t be expected that no

disputes will ever arise in a commonwealth. The best

thing is for complaints to be "freely heard, deeply

considered, and speedily reformed." That is "the utmost

bound of civil liberty . . . that wise men look for."

- "He who freely magnifies what hath been nobly

done and fears not to declare as freely what might be

done better, gives ye the best covenant of his

fidelity."

- Private, learned, individuals have been

respectfully heard by governments before: Isocrates

wrote to persuade Athens to change its current form of

government.

- The Parliament of England will only make

itself seem all the wiser by respectfully hearing

Milton’s argument.

- " . . . by judging over again that Order which

ye have ordained to regulate Printing: that no book,

pamphlet, or paper shall be henceforth printed unless

the same be first approved and licensed by such, or at

least one of such as shall be thereto appointed."

|

|

The Four Major

Arguments

- Who are the inventors of licensing?

The Catholic church.

- What is to be thought of reading? It is a necessary

acquisition of knowledge of good and evil in a fallen world.

- This Order is ineffectual in suppressing

"scandalous, seditious, and libelous books."

- This Order will discourage learning and the pursuit

of truth.

Argument #1

- In Athens, only two types of writings

were suppressed by the civil powers: blasphemous/atheistic

writings and libelous writings.

- Protagoras was banished and his books were burned

"for a discourse . . . confessing not to know whether there

were gods, or whether there were not."

- " . . . against defaming, it was decreed that none

should be traduced by name, as was the manner of Vetus

Comedia" [Old Comedy—Aristophanes, et. al.—this law endured

only from 440-39 to 438-37, and Aristophanes was famous for

"traducing" by name; he was especially fond of "traducing"

fellow-playwright Euripides and the politician Cleon by

name].

- The same holds true for Rome (before its descent

into tyranny).

- Naso (Ovid) was banished by Augustus not for

indecent poems but for an intrigue with Augustus’

granddaughter, Julia.

- "Naevius was quickly cast into prison for his

unbridled pen" because he had attacked Scipio and the

aristocratic party in his plays.

- Even the earliest Christian emperors did not depart

from this relatively tolerant position.

- Books of those accused of heresy were not

prohibited until and unless those accused were "examined,

refuted, and condemned in the general councils."

- Books by "heathen authors" were not forbidden in

any way until 400 AD, when bishops were restricted from

reading heathen writers (though they might still read—for

the purpose of later refuting—heretical works).

- Early councils and bishops only declared certain

books "not commendable" rather than forbidden until 800 AD.

After this the Popes began prohibiting certain works. Martin

V (1417-1431) issued a bull in 1418 calling for the

excommunication of any who read heretical works. Indexes of

forbidden works followed. Paul IV issued the first in 1559.

- The Catholic church is the inventor of the licensing

of printing: "their last invention was to ordain that no book,

pamphlet, or paper should be printed . . . unless it were

approved and licensed . . . thus ye have the inventors and the

original of book-licensing . . . from the most antichristian

council and the most tyrannous inquisition that ever

inquired."

Argument #2

- Moses, Daniel, and Paul were skillful in all the

learning of the Egyptians, Chaldeans, and Greeks,

respectively. This can only have been through prodigious

reading.

- Julian the Apostate (emperor from 361-363) forbade

Christians the reading of heathen writers. (Seems a weak

point, but the contention is that if an apostate forbids

reading classical literature, then it must be good for

faithful Christians to read.)

- Dinoysius Alexandrinus—a pious and learned early

Christian—read heretical books in order to be able to refute

the arguments therein. When challenged by "a certain

presbyter," he was in a quandary until he received a vision:

"Read any books whatever come to thy hands, for thou art

suficient both to judge aright and to examine each matter."

- Bad books may serve a "discreet and judicious

reader" to "discover, to confute, to forewarn, and to

illustrate."

- Solomon writes that much reading is "a weariness to

the flesh," but it is not therefore unlawful.

- The burning of books at Acts 19:19 was a voluntary

act—not mandated by any magistrate.

- Good and evil are almost inseparable in this

world—in this world, how can one have wisdom to choose good

without "the knowledge of evil"? "Since, therefore, the

knowledge and survey of vice is in this world so necessary to

the constituting of human virtue, and the scanning of error to

the confirmation of truth, how can we more safely and with

less danger scout into the regions of sin and falsity than by

reading all manner of tractates and hearing all manner of

reason? And this is the benefit which may be had of books

promiscuously read."

- Controversial books (of religion) are more a danger

to the learned than to the ignorant: "It will be hard to

instance where any ignorant man hath been ever seduced by

papistical book in English, unless it were commended and

expounded to him by some of that clergy."

- Licensing is a vain and impossible attempt, like

"the exploit of a gallant man who thought to pound up the

crows by shutting his park gate."

Argument #3

- No well-constituted nation or state ever used "this

way of licensing."

- Plato, in his Laws, spells out such a system,

but for an imaginary state. Plato—in reality—was a

transgressor of his own (imagined) laws: a writer of dialogues

and a reader of Aristophanes (whom he supposedly recommended

to Dionysius, the Tyrant of Syracuse [367-356 BC]).

- If printing must be regulated, so must all other

trades and arts.

- Who shall decide? Who shall set the absolute

standards?

- It is no good "to sequester out of the world into

Atlantic [Francis Bacon] and Utopian [Thomas More] polities,"

rather, we must "ordain wisely as in this world of evil, in

the midst whereof God hath placed us unavoidably."

- The "great art" of a commonwealth lies in knowing

what to restrain and forbid, and what to leave to private

conscience. Punishment and persuasion must be correctly

balanced.

- God gave man reason and freedom to choose.

Otherwise, Adam would have been "a mere artificial Adam." God

created passions within us so that we need to temper them in

and through virtue (tempering the passions is virtue).

By removing the causes/objects of sin, we remove the

opportunities for the acquisition, generation, and practice of

virtue: "how much we thus expel of sin, so much we expel of

virtue."

Argument #4

- To distrust the honesty and judgment of a "free and

knowing spirit" to the point of not counting him "fit to print

his mind without a tutor and examiner" is a great indignity.

- If no years of experience, learning, and industry

can bring a man "to that state of maturity as not to be still

mistrusted and suspected . . . [it is] a dishonor and

derogation to the author, to the book, to the privilege and

dignity of learning."

- How can a man teach with authority if all he teaches

is under the authority of a licenser?

- Francis Bacon: "Authorized books are but the

language of the times." Even if a licenser is especially

judicious and perceptive, the function of his office requires

that he license nothing "but what is vulgarly received

already."

- This distrust is an "undervaluing and vilifying of

the whole nation."

- It is a reproach to the people: "if . . . we dare

not trust them with an English pamphlet, what do we but

censure them for a giddy, vicious, and ungrounded people . .

. ?"

- It is a reproach to ministers: "That after all

this light of the Gospel . . . they should still be

frequented with such an unedified, and laic rabble . . . "

- Description of meeting Galileo: "a prisoner to the

Inquisition for thinking in astronomy otherwise than the

Franciscan and Dominican licensers thought."

- The complaints of the learned against the

Inquisition are now being made by the learned against the

Parliament’s order of licensing.

- The general murmur: if we are so suspicious of men

"as to fear each book . . . before we know what the contents

are," then we are facing "a second tyranny over learning."

This will soon show that the current presbyters (who had only

recently been silenced by the then-dominant Anglican

hierarchy) are just the same ("name and thing") as the old

bishops. Meet the New Boss. Same as the Old Boss.

- When the bishops were being fought against, freedom

of publishing was a good thing (according to the presbyters),

but now that the bishops have been defeated, suddenly

publishing must be licensed. How convenient.

Conclusion

- England is the new chosen nation of God.

- "Why else was this nation chosen before any other,

that out of her as out of Sion should be proclaimed and

sounded forth the first tidings and trumpet of reformation

to all Europe?"

- "God is decreeing to begin some new and great

period in his Church, even to the reforming of reformation

itself. What does he then but reveal himself to his

servants, and, as his maner is, first to his Englishmen?"

- England is an earthly type of the City of God.

- "Behold now this vast city, a city of refuge, the

mansion house of liberty, encompassed and surrounded with

his protection."

- The English people are potentially a "nation of

prophets, of sages, and of worthies." Only "wise and faithful

laborers" are needed to actualize this potential.

- "Where there is much desire to learn, there of

necessity will be much arguing, much writing, many opinions;

for opinion in good men is but knowledge in the making."

- Analogy to the building of the temple in Solomon’s

day: "when every stone is laid artfully together, it cannot be

united into a continuity, it can but be contiguous in this

world."

- The strength of the church lies in the unity of

diverse (but not too diverse) elements: "the perfection

consists in this, that out of many moderate varieties and

brotherly dissimilitudes that are not vastly disproportional,

arises the goodly and graceful symmetry that commends the

whole pile and structure."

- The "time seems come . . . when . . . all the Lord’s

people, are become prophets."

- The carrying on of these intellectual disputes even

during a time of civil war, when the forces of Charles I

threaten, is a sign of faith in the good government of

Parliament. (Thus commences the kiss-Parliament’s-ass

section.)

- The people became free to write and speak because of

the liberty that the "valorous and happy counsels [of

Parliament] have purchased." The people cannot grow less

learned and less inclined to write and speak unless Parliament

revert to tyrannous ways, "as they were from whom ye have

freed us.’

- Let Truth and Falsehood grapple in the open. Truth

will win.

- Doctrine of (limited) tolerance: "if all cannot be

of one mind—as who looks they should be?--this doubtless is

more wholesome, more prudent, and more Christian, that many be

tolerated rather than all compelled."

- This "many" does not include Catholics (or

non-Christians): I mean not tolerated popery and open

superstition, which, as it extirpates all religions and civil

supremacies, so itself should be extirpate . . . but those

neighboring differences, or rather indifferences, are what I

speak of, whether in some point of doctrine or of discipline."

- If the men who appear to be schismatics are indeed

wrong, why not debate them openly? If they are not wrong, and

are doing the work of God (the "Gamaliel" argument), "no less

than woe to us while, thinking thus to defend the Gospel, we

are found the persecutors."

- If nothing else will work, "it would be no unequal

distribution . . . to supress the supressors themselves."

To set right the wrong that has been

done is the highest and wisest thing that Parliament can do.

|

The Atheist Milton

Michael Bryson

(Ashgate Press, 2012) |

|

Basing his contention on

two different lines of argument, Michael Bryson posits that John

Milton–possibly the most famous 'Christian' poet in English literary

history–was, in fact, an atheist.

First, based on his association with Arian ideas (denial of the

doctrine of the Trinity), his argument for the de Deo theory of

creation (which puts him in line with the materialism of Spinoza and

Hobbes), and his Mortalist argument that the human soul dies with

the human body, Bryson argues that Milton was an atheist by the

commonly used definitions of the period. And second, as the poet who

takes a reader from the presence of an imperious, monarchical God in

Paradise Lost, to the internal-almost Gnostic-conception of God in

Paradise Regained, to the absence of any God whatsoever in Samson

Agonistes, Milton moves from a theist (with God) to something much

more recognizable as a modern atheist position (without God) in his

poetry.

Among the author's goals in The Atheist Milton is to account

for tensions over the idea of God which, in Bryson's view, go all

the way back to Milton's earliest poetry. In this study, he argues

such tensions are central to Milton's poetry–and to any attempt to

understand that poetry on its own terms.

|

|

The Tyranny of Heaven

Milton's Rejection of God as King

Michael Bryson

(U. Delaware Press, 2004)

|

|

The Tyranny of Heaven argues for a new way of reading the figure of

Milton's God, contending that Milton rejects kings on earth and in heaven.

Though Milton portrays God as a king in Paradise Lost, he does this

neither to endorse kingship nor to recommend a monarchical model of deity.

Instead, he recommends the Son, who in Paradise Regained rejects

external rule as the model of politics and theology for Milton's "fit

audience though few." The portrait of God in Paradise Lost serves as

a scathing critique of the English people and its slow but steady

backsliding into the political habits of a nation long used to living under

the yoke of kingship, a nation that maintained throughout its brief period

of liberty the image of God as a heavenly king, and finally welcomed with

open arms the return of a human king.

Review of Tyranny of

Heaven |

|

|

|

| |